Tim Side, CFA – Investment Strategist

Chris Kamykowski, CFA, CFP® – Head of Investment Strategy and Research

It is a sort of cruel irony that as we approach the 100-day marker since President Trump’s inauguration and expected moves to “Make America Great Again”, that investors are questioning whether the era of US exceptionalism is over. Of course, there are differing views on what a “great” or “exceptional” US looks like, but regardless of one’s political view and beliefs regarding the current administration’s actions, there is no denying that markets, especially US markets, continue to be roiled by current policy proposals.

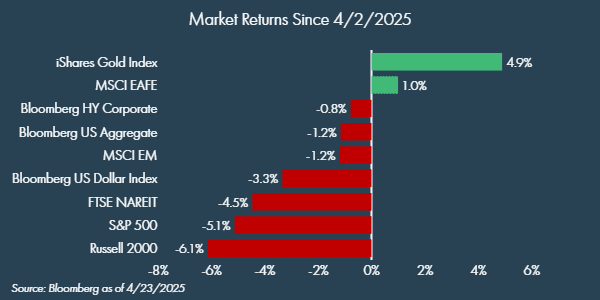

As mostly US-based investors, charts like the above hold little in the way of good news, though numbers have improved over the last couple of days. Of course, we can (and have) point to the fact that diversification is working; sentiment is not always reflective of what’s actually happening; and drawdowns like these are normal. However, inevitably these explanations are met with the question of, “But what if this time is different? Doesn’t ongoing falling sentiment create a negative feedback loop which affects economic growth?” To be sure, the circumstances around any historical event always hold some degree of “difference”, but just as often, there are similarities to past events in history. Mark Twain’s famous quip of “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” is a good summation of this fact.

There is no doubt that recent policy decisions are taking us into seemingly uncharted waters for many investors, but this is not the first time that policy decisions have roiled markets and called into question the exceptionalism of the US. So, while we can’t predict the outcome of Trump 2.0, we can look to the distant past for moments that “rhyme”, to gain some perspective on how things could unfold……IF past is in any way prologue to the current environment.

Herbert Hoover: Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930)

“In 1930, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, in an effort to alleviate the effects of the… Anyone? Anyone?…The Great Depression, passed the… Anyone? Anyone? The tariff bill? The Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act. Which, anyone? Raised or lowered?… raised tariffs, in an effort to collect more revenue for the federal government. Did it work? Anyone?… Anyone know the effects? It did not work, and the United States sank deeper into the Great Depression.”

-1986 Film: Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

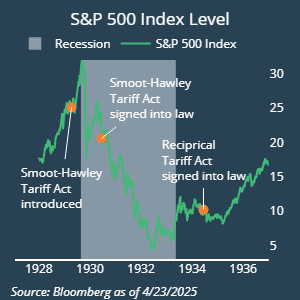

In the late 1920s, American farmers faced increasing competition and oversupply issues as European farmers recovered from World War I, prompting the 1928 Republican candidate Herbert Hoover to promise an increase in tariffs on agricultural goods. After the stock market crashed in 1929, additional pressure arose for greater protectionism, resulting in a much broader tariff bill (the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act) being passed through Congress and signed by President Hoover in June of 1930.

While certainly not the cause of the Great Depression, at best, these actions failed to alleviate economic pain and, at worst, contributed to a deeper economic slump as other countries applied reciprocal tariffs and global trade sharply declined. These actions also led to greater power given to the Executive branch (then President Roosevelt after defeating Hoover) to manage tariffs given a desire to roll back tariffs.

John F. Kennedy: US Steel Showdown (1962)

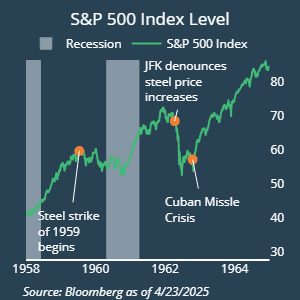

In 1959s, the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) went on strike for nearly four months, demanding higher wages amidst a backdrop of “record profits” and “stagnant wages”. Within two months of the strike, the Department of Defense expressed concerns that there would not be enough steel in the event of a crisis, ultimately driving President Eisenhower to invoke the Taft-Hartley law to bring workers and steelmakers to an agreement. While an agreement was reached, the shortage of steel sent companies looking abroad for additional sources of steel.

In 1962, as the 1959 agreement was coming to an end, steel companies initially agreed to marginally raise wages without increasing prices. Ten days later, however, they announced a 3.5% increase in prices, infuriating President Kennedy who publicly denounced the increases, calling them “a wholly unjustifiable and irresponsible defiance of the public interest”. Kennedy’s Administration put immense pressure on companies to lower prices – pressure to which the steel companies ultimately yielded to. While no recession occurred, the S&P 500 fell more than 20% on concerns that Kennedy was anti-business, only recovering following the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Richard Nixon: Closing the Gold Window (1971)

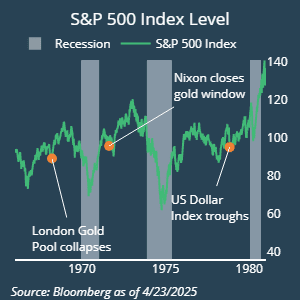

The creation of the Bretton Woods system in 1944 resulted in an agreement for several countries to fix their currency rates to the US dollar, which in turn was fixed to gold. In the 1960s, the US’s balance of payments deteriorated alongside an increase in demand for converting dollars to gold as European and Japanese exports became more competitive. By the early 1970s, the US was extremely vulnerable to a run on gold and a loss of confidence in the US’s ability to meet its obligations, threatening the dollar’s position as the reserve currency.

At home, the US was facing inflation combined with rising unemployment – a central banker’s worst nightmare. To address these issues, President Nixon announced the closure of the gold window on August 15, 1971, meaning governments could no longer exchange their dollars for gold, in addition to a 90-day freeze on wages and prices in an attempt to check inflation. Lastly, Nixon announced an import surcharge (tariff) of 10% to keep American made products competitive.

The actions initially had a positive impact on the US economy, as employment stabilized, inflation fell, and stocks rose. Ultimately, though, the actions failed to provide a long-term solution as an accommodative monetary policy laid the groundwork for another wave of inflation. While the S&P 500 bottomed in the mid-70s, the US dollar continued to weaken, with the US Dollar Index falling 34% from a peak in 1969 to its trough in 1978.

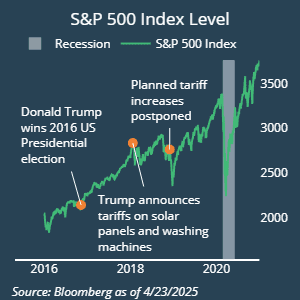

Donald Trump: China Trade War 1.0 (2018)

Fresh off a political win with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, President Trump shook markets with the announcement of tariffs on solar panel and washing machine imports from China, kicking off a trade war with China and a renegotiation of NAFTA with Mexico and Canada to achieve the USMCA. Similarly to today, markets reacted poorly, though it’s only fair to note that the Fed was also in the midst of a rate hiking cycle, creating a monetary policy headwind for markets. Relative to today’s trade war, 2018 was much more targeted to specific goods from China and the Administration had started coming off its harder rhetoric by the end of the year.

Similar to today, Trump expressed frustration with Fed Chair Jerome Powell and rumors circulated on whether he would be fired. Markets seized up in December of 2018, before recovering later in the month as the Fed worked out some “financial plumbing issues” and Trump stated that he was not going to fire Powell. In mid-2019, Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed on a “truce”, providing further stability for markets before the COVID-19 Pandemic.

A handful of paragraphs cannot do full justice to the point we are trying to make: American history is filled with policy actions that markets don’t always like. And yet, fortunately for investors, the exceptionalism of the United States is not attributed to any one president, rather it’s attributed to a democratic governmental structure and a capitalistic system that incentivizes people to take risks, lose money, and fail – all within the rule of law.

To be sure, the carnage wrought on the markets by sporadic Truth Social posts can undercut the very essence of why investors have flocked to the US market. As seen in the examples above, policy changes, right or wrong, are not always welcomed by markets. This is clearly seen today and amplified by the rapid changes in tone from the top.

However, by design, while it can certainly be damaged, the exceptionalism of the United States of America cannot be brought down by one person. Assuming the reports[1] are accurate – that more than 75 nations have reached out to the White House to negotiate deals – speaks to the importance of the US in global trade. Confidence may be shaken, but it has not been permanently destroyed – at least not yet.

History ultimately will judge the actions made today as to whether they were detrimental to US exceptionalism or not. The US still has fundamental underpinnings to remain exceptional. The main question today on anything surrounding policy is will cooler heads prevail to augment policy that – while perhaps containing merit to a degree – require a defter hand at implementation to achieve long-term goals? For now, we remain wedded to the Art of the Deal tactics.

[1] https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2025/04/22/will-trump-negotiate-tariffs-jd-vance-says-president-wants-to-rebalance-global-trade-but-no-deals-reached-yet/

DISCLOSURES

© 2025 Advisory services offered by Moneta Group Investment Advisors, LLC, (“MGIA”) an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). MGIA is a wholly owned subsidiary of Moneta Group, LLC. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply a certain level of skill or training. The information contained herein is for informational purposes only, is not intended to be comprehensive or exclusive, and is based on materials deemed reliable, but the accuracy of which has not been verified.

Trademarks and copyrights of materials referenced herein are the property of their respective owners. Index returns reflect total return, assuming reinvestment of dividends and interest. The returns do not reflect the effect of taxes and/or fees that an investor would incur. Examples contained herein are for illustrative purposes only based on generic assumptions. Given the dynamic nature of the subject matter and the environment in which this communication was written, the information contained herein is subject to change. This is not an offer to sell or buy securities, nor does it represent any specific recommendation. You should consult with an appropriately credentialed professional before making any financial, investment, tax or legal decision. An index is an unmanaged portfolio of specified securities and does not reflect any initial or ongoing expenses nor can it be invested in directly. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. All investments are subject to a risk of loss. Diversification and strategic asset allocation do not assure profit or protect against loss in declining markets. These materials do not take into consideration your personal circumstances, financial or otherwise.

DEFINITIONS

The S&P 500 Index is a free-float capitalization-weighted index of the prices of approximately 500 large-cap common stocks actively traded in the United States.

The Russell 2000® Index is an index of 2000 issues representative of the U.S. small capitalization securities market.

The MSCI EAFE Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization index designed to measure the equity market performance of developed markets, excluding the U.S. and Canada.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index is a float-adjusted market capitalization index that consists of indices in 21 emerging economies.

The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is an index, with income reinvested, generally representative of intermediate-term government bonds, investment grade corporate debt securities and mortgage-backed securities.

The Bloomberg US Corporate High Yield Bond Index measures the USD-denominated, high yield, fixed-rate corporate bond market. Securities are classified as high yield if the middle rating of Moody’s, Fitch and S&P is Ba1/BB+/BB+ or below. Bonds from issuers with an emerging markets country of risk, based on the indices’ EM country definition, are excluded.

The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index tracks the performance of a basket of ten leading global currencies versus the US Dollar. Each currency in the basket and their weight is determined annually based on their share of international trade and FX liquidity.

The FTSE Nareit All Equity REITs Index is a free-float adjusted, market capitalization-weighted index of U.S. equity REITs. Constituents of the index include all tax-qualified REITs with more than 50 percent of total assets in qualifying real estate assets other than mortgages secured by real property.

The iShares COMEX Gold Trust Intraday Indicative Value Index aims to track the price of gold via the LBMA gold price.